By all estimations, the video game market was expected to contract once the COVID-19 lockdowns ended but even the worst-case scenarios for a return to normalcy predicted net growth when compared to pre-pandemic levels.

Instead, a perfect storm of global political and macroeconomic factors, along with executive hubris, left us in a state of disarray and despair.

So how did 2023 despite being arguably one of the best years for games, become one of the worst for those who make games happen at the same time? And why are we still feeling the pinch?

What does a ‘generation’ mean anymore?

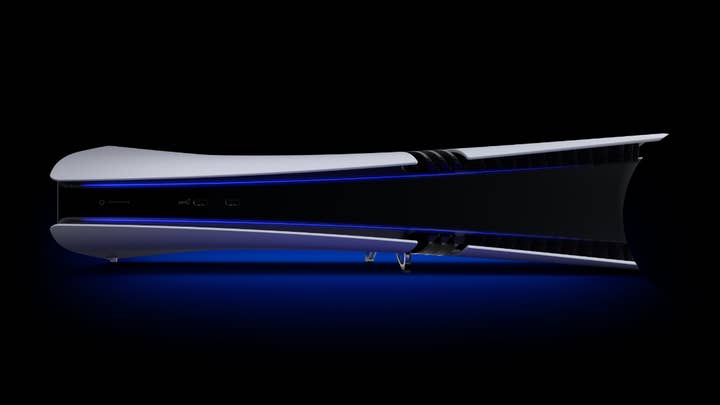

Beginning in the seventh generation, Microsoft and Sony began taking a page out of Nintendo’s handheld hardware playbook. Mid-generation refreshes became a motivating force for living room consoles, in part out of necessity.

This has created a set of expectations in the market among executives and investors. For two generations we’ve seen a resurgence in hardware spending that requires a specific set of circumstances: component cost savings, realizing manufacturing efficiencies, and a global economy that allows for price cuts rather than hikes. A global pandemic, an escalation of armed conflict, and an inflation crisis have all worked in opposition to this pattern repeating in the current hardware generation.

“2024 in particular seems to be the year where pricing has become more of a challenge,” Mat Piscatella, executive director and video game industry advisor at Circana, writes over e-mail. “Hardware spending in the US is down 30% for the year ending May when compared to the same period in 2023. That’s not great! And while some of that decline can certainly be attributed to the aging Switch device nearing the end of its lifecycle, sales of PlayStation 5 and Xbox Series X/S have also declined sharply so far this year.

“Combined with a less commercially appealing slate of new games when compared to 2023 (yes, there have been some hits in 2024, but not at the scale the market experienced last year – at least thus far) it is reasonable to assume that extended aggressive pricing may be a driving factor.”

“Sony and Microsoft can’t allow these declines to continue at these rates until 2027 or 2028 (or whenever the next devices and/or services arrive)”

Mat Piscatella, Circana

It would be difficult for ninth generation “Pro”-style releases to succeed at the same scale as the past two generations given all of these factors. The lack of launch model price downward movement means there’s less room for more powerful Pro models at an accessible entry fee. The announcement of the PlayStation 5 Pro at $699.99 (plus a $79.99 physical media drive) exemplifies the challenge the hardware market is facing. Pro models were always aimed at the center of the core segment, but with pricing this high, the target audience is even more focused. The higher price will severely limit reach and player adoption. This, in turn, would mute the number of used launch consoles entering the market.

With no price drops and a restricted supply of pre-owned hardware, in combination with macroeconomic forces, this generation simply is not as affordable at this point in the cycle compared to the PS4 and Xbox One era. This is a large part of the reason only 50% of PSN accounts activated on PlayStation 4s have made the move to PlayStation 5. And while PS5 is only trailing PS4 sales slightly as of March 31, 2024 (59 million PS5s vs 60 million PS4s), Piscatella and Circana’s outlook on hardware sales for the rest of 2024 isn’t terribly rosy. However, console manufacturers may be starting to budge a bit.

“We’re already starting to see some discounting happening, and really both Sony and Microsoft can’t allow these declines to continue at these rates until 2027 or 2028 (or whenever the next wave of devices and/or services arrive),” Piscatella explains.

“A couple of things will really impact how things go: Nintendo’s next hardware device, expected to arrive next year, could significantly disrupt the market. Of course, not much is known about this device beyond rumor, but a highly successful new Nintendo device could apply downward pricing pressure across other devices. But we’ll have to wait and see.

“Many are expecting (hoping) that Grand Theft Auto 6 will encourage a wave of mass market adoption, even at these higher price points. As the launch of that game goes, so could what happens with the console hardware offerings. There are signs suggesting that younger players are choosing PC and Mobile devices to play, rather than consoles. Price could certainly be an issue here, but it may be more about the games that these folks are playing (Fortnite, Minecraft, Roblox, etc.) and how they are not reliant on having new console hardware to experience.”

All of this is just table setting for the real challenges facing the industry, though. While war and the totality of the global economy might be outside the sphere of influence of AAA executives, these factors exacerbated a short-sighted strategy built on the belief that the COVID-19 boom would last forever (or at least rocket the industry to new heights of profit).

Let the good times roll and roll and… oops

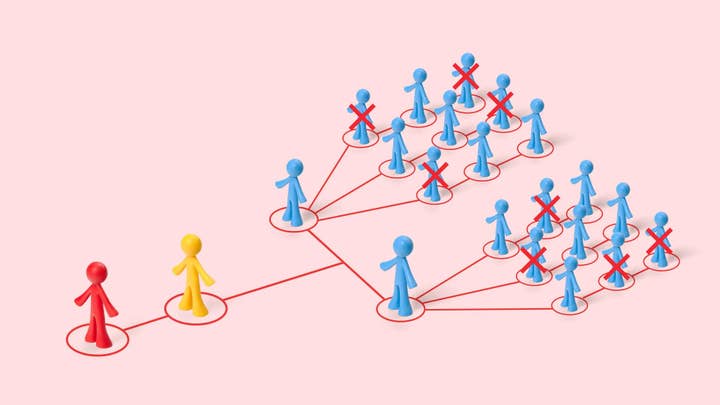

Over the last decade, publishers have become intoxicated by the staying power of Games-as-a-Service (GAAS). The best way to monetize a player is to keep them engaged through expansions. Seasonal content and battle passes have made this even more appealing, creating a fully greased flywheel to reach into people’s pocket and keep them spending on the same games.

There is one problem with this strategy, though: time is finite. As publishers greenlit more and more live service games, players became unable to keep up. The downside of incentivizing players to become heavily invested in one or two games is that it worked.

According to Newzoo’s 2024 PC and Console Gaming report, 61% of playtime in 2023 was attributed to games more than six years old. Minecraft, Grand Theft Auto V, a variety of Call of Duty games, Fortnite, and more have their hooks deep in players, and they are not letting go.

“The switching costs are so high,” consultant and Nocturne Games partner Jason Della Rocca says, referring to the monetary, psychological, or intangible cost of leaving one option for another. Because players invest so much time and money through battle pass and cosmetic purchases, the more impactful moving to a new service game feels. Especially with younger players seeing games with strong social elements as their third space (like a playground or library), there’s a deep sense of connection.

“Switching costs on Roblox are very high,” Della Rocca explains. “Switching costs on Fortnite are very high. So yeah, you do need to factor that. It kind of goes into how you build the game and which audience you’re going after.”

Even with understandable development delays as studios pivoted to a “working under quarantine” model, publisher coffers overflowed. Investors started asking questions, wondering how things were going to change when we could finally poke our heads outside safely into a post-COVID world.

The answers were optimistic.

We’d see a downturn as part of a “return to normalcy,” but we’d be in a better position than we were in 2019, before the pandemic. It was safe to spend that cash to strengthen portfolios, continuing an arms race that started in 2013.

Those that didn’t acquire, spun up new teams and grew their headcount. Pandemic prosperity in the video game industry inspired a tidal wave of hiring. As publishers leveraged their existing and new studio holdings, they pushed more and more “forever games” out the door. Players simply could not keep up.

“Leadership may be sitting in LA, but then the work will be split between crews in Brazil, India and maybe Vietnam. Because four people in LA will cost you just as much”

Jason Della Rocca, Execution Labs

In the first week of February 2023, the GAAS sector was shaken. In a bloodbath that has been labeled the “GaaSacre,” eight high-profile live titles were either canceled or put into an “end of life” phase. These include EA’s Apex Legends Mobile and Battlefield Mobile, Smilegate’s Crossfire X, Square Enix’s Dragon Quest: The Adventure of Dai, Iron Galaxy’s Rumbleverse, Konami’s Among Us-like Crimesight, and Velan’s Knockout City. Even VR players felt the pinch as Meta-owned Ready at Dawn announced it was sunsetting Echo VR.

Since then, we’ve seen the tolerance for risk on service titles get smaller and the runway made shorter. Today, it’s not uncommon to see games get less than a year to prove they can sustain an audience. If a title doesn’t launch with big concurrent users and monetize well, it isn’t likely to last more than a handful of months. No game is greater evidence of this than Concord, with a reported eight years in development and a budget of more than $100 million. Sony launched Firewalk Studios’ hero shooter on August 27 before removing it from sale and scrubbing any mention of it from the PlayStation website on September 6. Live service games require a healthy player base to warrant further investment, and Concord peaked at only 697 concurrent players.

Combined with unanticipated global events that sent the world into the dreaded combination of inflation and contraction, the costs of goods and services – including manufacturing and shipping – climbed, making it more difficult for consumers to purchase as much or as frequently.

In a piece written for the ACM Games: Research and Practice Academic Journal, analyst Amanda Farough likened this to the dotcom bust in the early 2000s. And, in many ways video game companies were able to go on spending sprees because of the dotcom crash and the global financial crisis that happened at the end of that decade.

“This free flow of capital during COVID-19 was a continuation and expansion of corrective measures taken by governments to mitigate the 2008-09 subprime mortgage crisis in the United States that led to the 2008 Global Financial Crisis,” Farough writes. “Thanks to low interest rates (a.k.a. ‘cheap debt’), we saw big bet after big bet in a non-stop deluge of investment and acquisition announcements.”

The post-lockdown correction was more severe than executives anticipated. Publishers had over-indexed on service games, which suddenly weren’t uniformly perennial cash cows. And then the other shoe dropped on the wave of acquisitions that dominated the news for five years.

The good times came to a crashing halt in 2022.

An unprecedented video game industry labor crisis

The tricky thing about late-stage capitalism is that investors make unreasonable demands on corporations. In some ways, shareholders and institutional investors are like looter-shooter players; investments are a never-ending quest for “number go up,” they want it to go up forever – and it simply cannot. It’s not just about growth, though. Investors expect to see the rate of growth to increase year after year.

As the economy started to sour and growth slowed after the lockdown ended, executives began to worry. Shareholders and investors are not content if companies contract, even if the economic environment is treacherous. To counter this, executives pulled their favorite lever: layoffs.

While we don’t have exact numbers due to obfuscated reporting and news that doesn’t always spread far enough to catch reporters’ eyes, job losses since 2022 are nearing 30,000. Statista, a data and business intelligence firm, estimates that we lost 11,250 jobs in 2023. In the first six months of 2024, that number was nearly eclipsed.

Sony, Microsoft, EA, Take-Two, Ubisoft, Embracer Group, Paradox, Thunderful, TinyBulld and many others have all had a hand in the destruction, closing studios and displacing hundreds of employees. We’ve seen horror stories from people who moved across a continent for a job only to have that position eliminated in mere weeks. All the while, executives remain untouched, raking in large bonuses for keeping share value up at the expense of jobs.

Dozens of indie teams have had to give up their dreams and shutter their studios due to a challenging funding environment. Professional service providers in the game industry orbit are feeling the pinch, too, as budgets get slashed and everyone is being asked to do more with less. The state of the global economy is also creating a crisis in games media as jobs are disappearing at alarming rates. Even storied outlets like Game Informer, which was shut down by owner GameStop in August after 33 years, are unable to escape.

Publishers are mitigating risk by demanding developers present even more during the pitch phase. Instead of prototypes, developers are being forced to fund full vertical slices (a fully-functional, polished segment of a game that demonstrates all of its key systems). Where developers had been leaning on publishers for a full suite of communication support (PR, marketing, community, and social), now funders are expecting to see healthy community interest before signing deals.

“My hope is that this starts to cool off in the coming years and the next iteration of investing in games is more robust and able to support a wider variety of studios and content”

Kelly Wallick, 1up Ventures

“The rewards for a hit can be very high,” 1Up Ventures partner and community builder Kelly Wallick says. “In theory, this type of business should be well suited for [venture capitalists], which can take bold risks. But they need to be bold, calculated risks.

“One way to offset this is to better understand as much of the risks as you can, and one of these vectors is to have the founders that are pitching provide more product, more context and more conviction than they may have had to a few years ago. This can translate into all kinds of upfront risk for the founder, such as building a prototype, self-funding, building early community hype and traction, etc.

“The degree to which this needs to be done also relates to the general experience level of the founder. New talent will have more to ‘prove’ on the execution side and more experienced founders will have more to ‘prove’ on the startup mentality side for example.”

The pain is being felt worldwide. While eyes are often on Western teams, Asian studios and publishers are feeling the pain, too.

“Many of the same factors impacting game companies in the West have also led China-based companies to initiate mass layoffs and restructure their business to focus on a smaller portfolio of games with high revenue potential,” Niko Partners Director of Research Daniel Ahmad says.

“We’ve also seen a slowdown in video game-related deals being announced and closed over the past year or so. There are multiple reasons for this. Growth of video game companies has slowed globally. Interest rates are no longer as low as they once were. Investments in new technology areas related to gaming such as VR, Cloud Gaming, and Web3, among others, have not yielded expected results.”

The brain drain will be felt for years to come. We’re losing talented senior and mid-level developers to other industries. And there is no room for the flood of juniors coming out of game development education programs. The cost of capital has increased so severely, while venture capitalists and private equity have been burned by fad technologies. This means the typical groundswell of new indie studios operating on the back of equity funding isn’t happening this time around. Laid off staff have nowhere to go.

But there are some glimmers of hope that things may be starting to improve, if slowly.

Where do we go from here?

In a year that has seen multiple smaller titles, like Palworld, Helldivers II, and Enshrouded dominate player engagement, large publishers are still choosing to eschew experimentation and smaller investments. Instead, they are making bigger bets on fewer titles. Square Enix, EA, Nintendo, Microsoft, and more are all signaling further risk aversing by leaning into established franchises at larger scales.

With the cost of debt still so high, we’re seeing shifts in how funding is coming together for teams of all sizes.

“I’d say deals generally take longer, are for smaller amounts of money, and at lower valuations,” Wallick tells us. “Which means larger amounts of the companies are being sold for less money in equity rounds. Although it kind of seems like the pricing and raise amounts now are more aligned with how it looked prior to the bubble, so it might be better to think about it more as an equalization on that front than anything else. There are still fairly active pre-seed and seed funding, but the later, larger rounds have slowed.”

Similar shifts are happening in Asia, with Chinese companies taking a different approach. “Chinese companies have started focusing on internal expansion, through the creation of new studios, rather than the buying spree approach they took prior,” Ahmad explains.

However, the Middle-east and other areas are getting infusions of cash. Saudi Arabia is using the industry to sportswash its human rights reputation.

“The MENA region, particularly Saudi Arabia and the UAE, have strong government backing,” Ahmad says. “Both markets have looked to diversify their economy away from oil, with gaming and esports as notable growth sectors. This has led to the creation of dedicated policies and plans within Saudi Vision 2030 and the UAE Digital Economy Strategy such as Saudi Arabia’s National Gaming & Esports Strategy and Dubai’s Program for Gaming.

“This investment is leading to the creation of the largest esports tournament in the world, the buildup of dedicated game development studios in the region, and robust infrastructure to support gaming growth. While it’s still early for the region, it’s clear that this is a long-term strategy.”

“Growth of game companies has slowed globally. Interest rates are no longer as low. Investments in new technology areas related to gaming such as VR, Cloud Gaming, and Web3 have not yielded expected results”

Daniel Ahmad, Niko Partners

Della Rocca reflects that other regions are emerging, too, noting studios in Poland and Romania opening recently from notable talent and major investors, like Amazon Games. In addition to the cost of doing business in cities like Los Angeles, San Francisco, or London, the loosening of geographic restrictions is a major financial incentive.

“Everyone’s connected on Discord and Slack,” Della Rocca says. “Leadership may be sitting in LA, but then the work will be split between a crew in Brazil, a couple of folks in India and maybe some other folks in Vietnam. So you can optimize the limited cash you have. Because four people in LA will cost you just as much as 40 people in Brazil or something ridiculous like that.”

It’s not entirely hopeless out there. The industry will eventually stabilize and improve. Players are always going to want to play games. When and how this stabilization will happen is hazy. It’s dependent on executives, some of whom do not even play video games, often chasing trends like Web3 and AI rather than investing in people.

In a recent report, venture capital firm Konvoy Ventures notes that through the first half of 2024, deal value is down 7% from last year and the number of deals are down 12%. However, while growth and late-stage investments are still struggling, early-stage investment is starting to recover. This points to a positive turnaround in 2025 that could revitalize the indie startup scene.

Just as quickly as the industry swelled during COVID-19 and crashed in its aftermath, something else might surprise us and turn fortunes around once more.

“It feels like every handful of years some wildly unpredictable thing is happening in the world or in technology or in the economy that we’ve never seen before,” Wallick says. “So maybe the cycles of unexpected ‘perfect storms’ are not as rare as we might think. We’ll just have no idea what those will be until they happen. And anyone who says they know the future most definitely doesn’t. Otherwise, what would any of us even be doing here? We could have just gone home by now!”

For the game industry to stabilize and thrive again, it must continue to expand efforts to reach as many players as possible where people play. That means lifting up underserved voices, leaning into representation, and fostering teams of all sizes. Wallick and so many others are looking forward to the turnaround.

“My hope is that this starts to cool off in the coming years,” she says. “And the next iteration of this kind of investing in the games space is more robust and more able to support a wider variety of studios and content – which hopefully leads to cooler games and more opportunities for players to find and connect with what they love.”