Setup of AAV capsid testing in human liver

We first investigated the possibility of long-term NMP with the commercially available OrganOx metra system20 (beyond the 24 h used clinically) using a steatotic and fibrotic human liver (steatotic liver 1 (SL 1); Extended Data Fig. 1a–c and Supplementary Table 1). We replaced 20% of the perfusate with PRBCs every 24 h or when the hemoglobin dropped to 6 g dl–1. We evaluated the perfused liver according to the same criteria used clinically for selecting transplantable livers by short-term NMP21. The liver was viable and functional for 103 h, as evidenced by lactate clearance (<2.5 mmol l–1), glucose metabolism (responsiveness to insulin) and pH (7.3–7.4), all measured in the perfusate, and bile production (>4 ml h–1; Extended Data Fig. 1d). In addition, the liver remained responsive to continuous infusion of a vasodilator by maintaining a stable hemodynamic profile (Extended Data Fig. 1e).

To optimize long-term NMP, we added basic renal function by incorporating a hemoconcentrator into the NMP circuit, which we tested in another steatotic liver (SL 2; Extended Data Figs. 1a and 2a). After 3 h of hemoconcentration, levels of blood urea nitrogen, creatinine and osmolality in the perfusate were reduced by about 20%, reflecting removal of waste metabolites (Extended Data Fig. 2b). We balanced electrolyte levels by replacing the hemofiltrate with isotonic dialysate (Extended Data Fig. 2c).

We also used perfusion of SL 2 to eliminate biases from our approach to AAV capsid evaluation. We removed residual plasma, which can include NAbs to AAV capsids27,28, by centrifugation-mediated washing of PRBCs29, after which NAbs to the AAV2, AAV5, AAV6, AAV8 and AAV-DJ capsids became nearly undetectable as assessed by luciferase-based neutralization assay (Extended Data Fig. 3a). We also excluded loss of AAV vectors by attachment to the surface of the silicone tubing in the NMP circuit30 (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Finally, we minimized the time required to detect functional transduction, that is, mRNA and protein expression by AAV vectors. We constructed a self-complementary AAV (scAAV) vector that expresses a fluorescent protein-encoding transgene from the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter. scAAV vectors express transgenes more rapidly than single-stranded AAV vectors because they bypass the need for second-strand DNA synthesis after uncoating of the viral particle in the nucleus31. The CMV promoter is ubiquitously active, which allows for comprehensive characterization of AAV capsid tropism32. Moreover, the CMV promoter provides rapid-onset and high-level transgene expression—it is subject to silencing in hepatocytes but only after 7 days33. To identify the earliest time point when functional transduction could be reliably detected, we intravenously injected scAAV vectors produced with AAV8, AAV5, AAV-LK03 and AAV6 capsids into mice. Expression of vector-derived mRNA and fluorescent protein increased moderately between 48 h and 7 days after injection, reflecting ongoing functional transduction, but the relative transduction efficiencies of the four AAV vectors were essentially the same between the two time points (Supplementary Fig. 2a,b). These results led us to use the scAAV-CMV vector for all subsequent experiments (Supplementary Table 2).

These results establish NMP as an experimental system for testing AAV capsids under physiological conditions in human livers and limit the critical perfusion time after AAV vector administration to 48 h.

Transduction profile of the AAV8 capsid in normal human liver

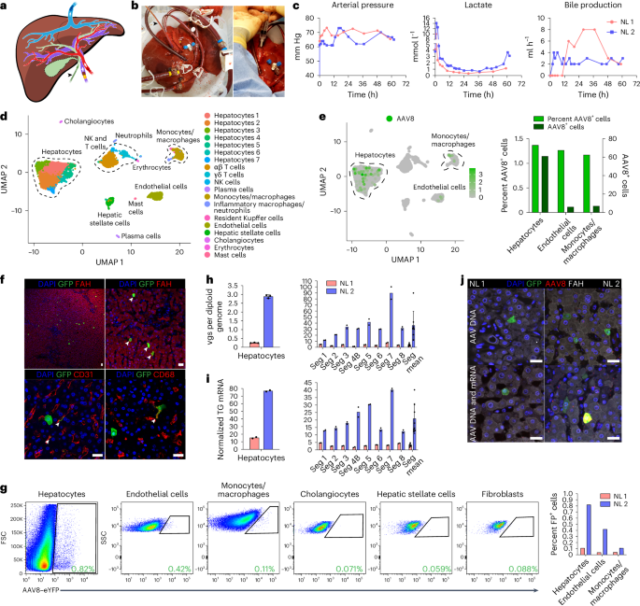

Using our optimized approach, we investigated the efficiency and specificity of hepatocyte transduction of a vector produced with the AAV8 capsid, which is most commonly used in clinical trials of liver gene therapy1, in two human livers that were histologically normal according to biopsies taken before NMP (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 1). Perfusate obtained before vector infusion contained a negligible amount of NAbs to the AAV8 capsid, confirming the efficacy of PRBC washing (Extended Data Fig. 3b). After achieving an optimal hemodynamic and metabolic profile at 12 h of perfusion, we infused 5.7 × 1012 vector genomes (vgs) of AAV8–enhanced green fluorescent protein (AAV8–eGFP) into normal liver 1 (NL 1) and 1.6 × 1013 vgs of AAV8–enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (AAV8–eYFP) into NL 2 through the portal vein (Fig. 1a–c, Extended Data Fig. 4a and Supplementary Table 2). These doses reflect the range given in clinical trials of liver gene therapy with AAV8 vectors3 but are calculated based on liver weight instead of body weight because biodistribution is not a factor in our system (Supplementary Table 1). We ascertained the functionality of these AAV vectors after intravenous injection into mice (Extended Data Fig. 5a). Declining vector DNA levels in the perfusate indicated uptake into the liver (Supplementary Fig. 4a–c). We ended NMP when the lactate level began increasing to ascertain a physiological state (48 h after AAV infusion for NL 1 and 50 h for NL 2; Fig. 1c and Extended Data Fig. 4a).

a, Cartoon showing cannulation of human liver and direction of flow in blood vessels and the bile duct (gall bladder removed). b, Images of cannulated and perfused NL 1 (left) and AAV8–eYFP vector infusion into the portal vein (right). Cannula colors are the same in a and b, where yellow indicates the portal vein, red indicates the hepatic artery, blue indicates the inferior vena cava, and the black arrowhead indicates the bile duct. c, Viability and function measured during NMP of NL 1 and NL 2. Of note, in NL 2, infusion of 1 U of PRBCs at 60 h precipitated an increase in lactate. In NL 1, bile production was not recorded between 0 and 11 h due to a mispositioned bile duct cannula. d, Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) of 6,959 liver cells analyzed by scRNA-seq and clustered according to cell identity; NK, natural killer. e, Left, distribution of AAV8+ cells in scRNA-seq. Right, percentage and absolute number of AAV8+ cells in each cell population. f, Immunofluorescence for GFP (AAV8), FAH (hepatocytes), CD31 (endothelial cells) and CD68 (monocytes/macrophages) in tissue samples from NL 2 after NMP. White arrowheads indicate cells positive for both GFP and the respective cell-type-specific marker; scale bars, 25 µm. g, Flow cytometry (left) with quantification (right) of AAV8-transduced cells released from NL 2 after 62 h of NMP; FP, fluorescent protein. h,i, Quantification of AAV vgs per diploid genome (h) and transgene (TG) mRNA expression (i) in isolated hepatocytes and tissue samples from NL 1 and NL 2. NL 1 received 5.7 × 1012 vgs and NL 2 received 1.6 × 1013 vgs. Values are presented as mean ± s.d. (n = 2 except n = 3 hepatocytes in h; technical replicates); Seg, segment; Seg mean, mean expression values of all eight segments. j, ISH of AAV vector DNA using an eGFP sense probe (top) and both AAV vector DNA and mRNA using an eGFP antisense probe (bottom) combined with immunofluorescence for GFP in tissue samples from NL 1 and NL 2; scale bars, 25 µm.

After NMP ended, we enzymatically released hepatocytes and nonparenchymal cells (NPCs), including endothelial cells, monocytes/macrophages, cholangiocytes and mesenchymal cells (hepatic stellate cells and fibroblasts), and analyzed them by single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq). Analysis of 6,959 cells from NL 2 showed 6 principal and 14 specific cell types (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 5a–e), with hepatocytes being most efficiently transduced by the AAV8 vector, closely followed by endothelial cells and monocytes/macrophages (Fig. 1e). Immunostaining of fluorescent protein-expressing cells in tissue sections and flow cytometry with optimized antibody panels (Extended Data Fig. 6a–d) confirmed the AAV8 capsid tropism identified by scRNA-seq independent of vector dose (Fig. 1f,g). Quantitative digital droplet PCR (ddPCR) showed dose-dependent differences in vector DNA and transgene mRNA in isolated hepatocytes and tissue samples of the eight liver segments from the two livers, with tight correlation between the two parameters (Fig. 1h,i). In situ hybridization (ISH) with sense or antisense probes targeting vector DNA or both vector DNA and transgene mRNA confirmed this result (Fig. 1j).

These results show that the tropism of the AAV8 capsid in the normal human liver includes endothelial cells and monocytes/macrophages in addition to hepatocytes. These results also establish that the AAV8 capsid affords efficient functional transduction in the human liver as evidenced by corresponding levels of physical vector cell entry and transgene expression, with scRNA-seq being equally as informative as flow cytometry.

Comparison of AAV capsids in normal and steatotic human livers

We compared the transduction profile of the AAV8 capsid with that of the AAV5, AAV-LK03 and AAV6 capsids, which are most commonly used in clinical trials of liver gene therapy1, and the AAV-NP59 capsid, which, based on studies in immune-deficient mice, has the strongest tropism for human hepatocytes34. To facilitate side-by-side comparison, for each capsid, we introduced a unique fluorescent protein-encoding transgene and expressed barcode into the AAV vector, allowing for distinction by flow cytometry, microscopy and ddPCR (Supplementary Fig. 6a–d and Supplementary Table 2). We ascertained that scRNA-seq reliably detects transgenes and barcodes (see Methods) and excluded that co-injection of AAV vectors produced with the different capsids alters the transduction efficiency of any individual capsid in mice (Supplementary Fig. 6e,f).

Before testing in human liver, we intravenously co-injected the AAV vectors at the same dose into wild-type mice and FRGN mice repopulated with human hepatocytes. Two days later, we enzymatically released hepatocytes and analyzed fluorescent protein expression by flow cytometry. We found a capsid-specific transduction efficiency of AAV8 > AAV6 > AAV5 > AAV-LK03 > AAV-NP59 in mouse hepatocytes and AAV-NP59 > AAV-LK03 > AAV8 > AAV6 > AAV5 in human hepatocytes (Extended Data Fig. 5b–h), which is in agreement with reports of species-specific hepatocyte tropism of these capsids10,11,12,13,34.

Because the anticoagulant heparin used for NMP in the clinical setting can reduce the transduction efficiency of the AAV-LK03, AAV6 and AAV-NP59 capsids35,36, we substituted low-molecular-weight heparin after screening alternative anticoagulants in mice (Supplementary Fig. 7a–c).

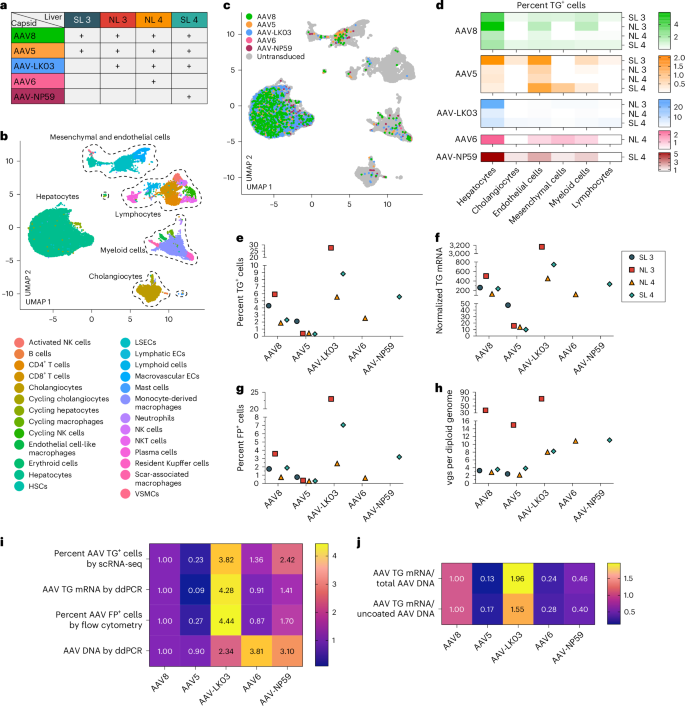

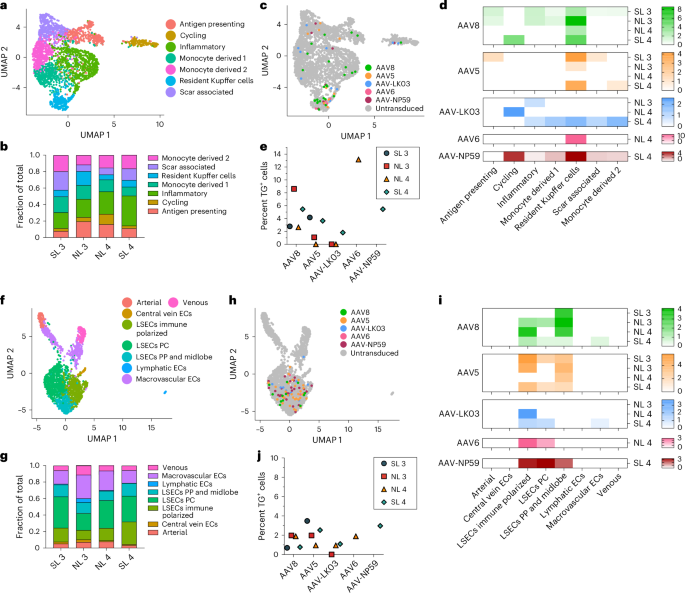

We co-infused AAV vectors produced with the five capsids into four human livers, two histologically normal (NL 3 and NL 4) and two steatotic (SL 3 and SL 4; Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 1). To contextualize our results, we sequentially introduced additional AAV vectors in combination with AAV8, which served as an internal control, with the AAV8, AAV5, AAV-LK03, AAV6 and AAV-NP59 capsids being tested in four, four, three, one and one livers, respectively (Fig. 2a). We co-infused AAV vectors at the same dose, ranging from 6.7 × 1011 vgs to 3.4 × 1013 vgs per vector between livers (Supplementary Table 2). Both normal and steatotic livers were viable, as assessed by analysis of liver injury and function in perfusate and cell death in tissue sections, and hemodynamically stable throughout NMP, up to and including the termination time of 60–73 h after AAV vector infusion (Extended Data Fig. 4a,b). We retrieved hepatocytes and NPCs at high yield from all livers, allowing for integrated clustering of 6 principal and 26 specific cell types by scRNA-seq (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 8a). All five AAV vectors primarily transduced hepatocytes. Among NPCs, endothelial cells and myeloid cells were most frequently transduced, whereas cholangiocytes, mesenchymal cells and lymphocytes showed low levels of transduction (Fig. 2c,d). Notably, AAV-LK03 was most specific for hepatocytes, with minimal transduction occurring in NPCs.

a, Assignments of AAV capsids to human livers for side-by-side comparison. SL 3 received 3.4 × 1013 vgs, NL 3 received 5.5 × 1012 vgs, NL 4 received 6.7 × 1011 vgs and SL 4 received 3.0 × 1012 vgs of each vector. Of note, the low-producing AAV6 capsid dictated the lower dose in NL 4. b, UMAP of 35,807 cells from four livers analyzed by scRNA-seq and clustered according to cell identity; ECs, endothelial cells; LSECs, liver sinusoidal endothelial cells; HSCs, hepatic stellate cells; VSMCs, vascular smooth muscle cells. c, UMAP showing cells transduced by AAV capsids. d, Heat map showing percent transduction by AAV capsids across cell populations. e,f, Quantification of AAV transgene mRNA-expressing hepatocytes by scRNA-seq (e) and ddPCR (f). g, Quantification of AAV fluorescent protein-expressing hepatocytes by flow cytometry. h, Quantification of AAV vector DNA (vgs) per diploid genome in hepatocytes by ddPCR. i, Heat map showing the relative levels of AAV vector mRNA, protein and DNA among five AAV capsids normalized to the levels of AAV8. The levels from four livers were averaged for each capsid. j, Heat map showing the relative levels of the ratio between AAV transgene mRNA and total AAV vector DNA from hepatocytes (top row) and AAV transgene mRNA and uncoated nuclear AAV vector DNA from tissue samples (bottom row). Levels were normalized to the levels of AAV8 and averaged from four livers for each capsid.

We next quantified capsid-specific transduction at the mRNA, protein and DNA levels in hepatocytes by scRNA-seq, flow cytometry and ddPCR. In hepatocytes, we found a functional transduction (mRNA and protein) efficiency of AAV-LK03 > AAV-NP59 > AAV8 ≥ AAV6 > AAV5 (mRNA range: 27.7% to 0.3%, protein range: 23% to 0.3%) and a physical transduction (DNA) efficiency of AAV6 > AAV-NP59 > AAV-LK03 > AAV8 > AAV5 (range: 70.9 to 2.2 vgs per diploid genome; Fig. 2e–i and Supplementary Fig. 9a–d). The relative transduction efficiency in the eight segments of each liver paralleled the levels in hepatocytes, which we confirmed in tissue sections by ISH of vector DNA and mRNA (Supplementary Figs. 10a–c and 11a–d). Detection of unique capsid barcode sequences alone by scRNA-seq further confirmed the capsid transduction hierarchy (Supplementary Fig. 10d). Notably, the functional transduction efficiency of AAV-NP59 was 55% less than that of AAV-LK03, the opposite of what has been reported in immune-deficient mice engrafted with human hepatocytes, which we independently confirmed34 (Extended Data Fig. 5e,f,h).

We also investigated capsid-specific differences in transcription efficiency by quantifying the ratio of AAV transgene mRNA to uncoated AAV vgs within nuclei, that is, DNA available for transcription (Supplementary Fig. 10e–g). Transcription efficiency was highest for AAV-LK03 and lowest for AAV5 (Fig. 2j).

These results show that the AAV-LK03 capsid transduces hepatocytes in human liver much more efficiently and specifically than the AAV-NP59, AAV8, AAV6 and AAV5 capsids. By establishing the superiority of AAV-LK03 for hepatocyte-targeted human liver gene therapy, our results highlight limitations of immune-deficient mice engrafted with human hepatocytes34. In addition, these results uncover capsid-specific effects on AAV vector transcription in the human liver, which aligns with reports of an epigenetic role of the AAV capsid37,38.

AAV capsid-specific effects of hepatocyte zonation and steatosis

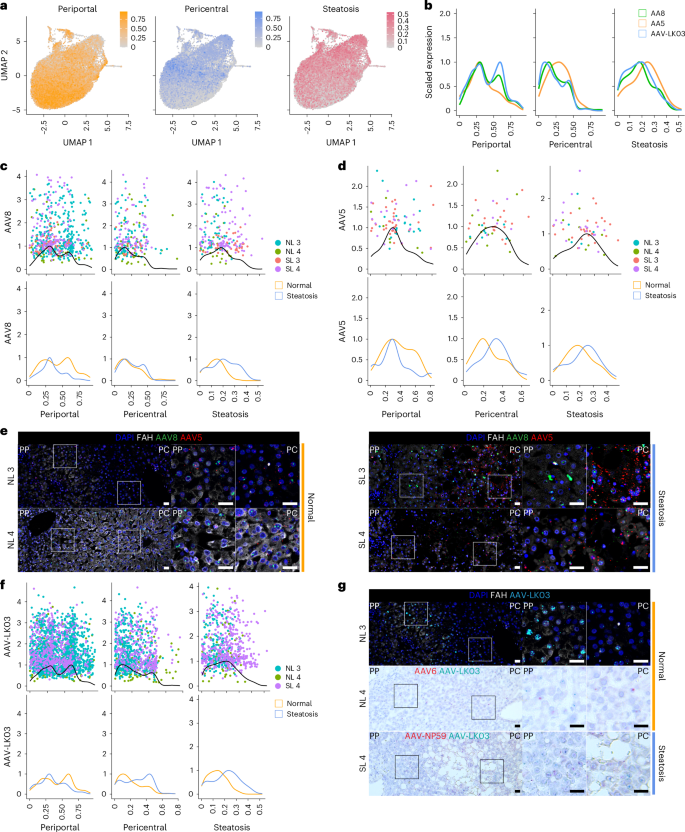

To determine whether any of the five AAV capsids preferentially transduces hepatocytes in a specific zone of the human liver and how this tropism may be altered in the setting of steatosis, we analyzed scRNA-seq data from 22,146 hepatocytes from NL 3, NL 4, SL 3 and SL 4. We generated a periportal and pericentral score derived from the expression of zonation markers conserved across all four livers to quantify the zonation enrichment on a per cell basis (Extended Data Table 1), which revealed a consistent pattern of functional zonation irrespective of disease state (Fig. 3a and Extended Data Fig. 7a). Similarly, in assessing the effect of steatosis on these parameters, we adopted a nonbinary approach to cell classification by scoring each cell individually based on expression of steatotic marker genes (Fig. 3a and Extended Data Table 1). This approach revealed a spectrum of steatosis, with normal livers containing some steatotic cells and steatotic livers containing some normal cells, and enabled us to identify CXCL8 as a highly specific and conserved marker of steatotic hepatocytes across normal and steatotic livers (Extended Data Table 1 and Extended Data Fig. 7b).

a, Gene module scores for periportal and pericentral zonation and steatosis applied to UMAPs of 22,146 hepatocytes from four livers analyzed by scRNA-seq. b, Kernel density estimation histograms of transgene-positive hepatocyte distribution across gene module scores. c, Kernel density estimation histograms of hepatocytes transduced by the AAV8 capsid across gene module scores (top) and separated by disease state (bottom). d, Kernel density estimation histograms of hepatocytes transduced by the AAV5 capsid across gene module scores (top) and separated by disease state (bottom). e, ISH of AAV8 and AAV5 vector DNA with sense probes in tissue samples; scale bars, 25 µm; PP, periportal; PC, pericentral. f, Kernel density estimation histograms of hepatocytes transduced by the AAV-LK03 capsid across gene module scores (top) and separated by disease state (bottom). g, ISH of AAV-LK03 vector DNA with sense probes in tissue samples. Kernel density estimation histograms for AAV6 and AAV-NP59 capsids are shown in Extended Data Fig. 7f; scale bars, 25 µm.

We also investigated whether the most steatotic hepatocytes exhibit altered transcriptomic signatures. We focused on hepatocytes from SL 4, the most steatotic liver by histologic score, because 42% of these hepatocytes clustered separately from the other livers despite integration (Extended Data Fig. 7c). These clusters were uniquely enriched for expression of genes in the NADPH reduction pathway (TXNRD1, GCLM, AKR1C1 and AKR1C2), which plays an important role in fatty acid biosynthesis39 (Extended Data Fig. 7d,e). Zonation was retained in these cells, consistent with it being altered only in end-stage liver disease40 (Fig. 3a and Extended Data Fig. 7a).

These results showed that our steatosis scoring method accurately reflects tissue histology and that our zonation scoring method is applicable to all livers regardless of steatosis severity. We applied these methods to determine the effects of steatosis on AAV capsid transduction at single-cell resolution. We first compared AAV capsid behavior by plotting hepatocytes transduced with the three capsids most commonly used in clinical trials against their respective zonation and steatosis scores (Methods and Fig. 3b). This analysis revealed higher periportal scores for AAV8 and AAV-LK03 than for AAV5, which conversely showed unique pericentral score enrichment. AAV5 transduction was associated with a higher steatosis score, which reflected its high pericentral score41 (Fig. 3b).

Next, we analyzed normal and steatotic livers separately to determine the contribution of disease state to zonation of AAV capsid transduction. Our scoring method showed that the weak periportal zonation of AAV8 was specific to normal livers (Fig. 3c), whereas pericentral zonation of AAV5 was specific to steatotic livers (Fig. 3d), which we confirmed in tissue sections by ISH of vector DNA (Fig. 3e) and/or mRNA (Supplementary Fig. 11a–d). We found differential expression of genes associated with steatosis and steatotic liver disease in hepatocytes exclusively transduced by AAV5. Pericentrally zonated LPCAT2 (ref. 42) and LPCAT1, genes involved in phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis and lipid droplet formation and remodeling43, were enriched, whereas FADS1, which protects hepatocytes from lipid accumulation44, and FADS2 were depleted in SL 3; C3AR1 and DUSP9, which regulate lipid accumulation45,46, were enriched in SL 4, and pericentrally zonated SLCO1B3 (ref. 47) was enriched in both steatotic livers (Supplementary Data 1). ISH confirmed that AAV5 favors steatotic pericentral hepatocytes by showing vector DNA (Fig. 3e) and/or mRNA (Supplementary Fig. 11a,d) accumulating in lipid-laden cells. There were also steatosis-dependent changes in AAV-LK03 zonation. The strong periportal zonation of AAV-LK03 observed in normal liver was lost in the setting of steatosis, where its pericentral zonation was increased, which we confirmed by ISH of tissue sections (Fig. 3f,g and Supplementary Fig. 11b–d). For AAV6, our zonation model and ISH showed weak periportal zonation in normal liver, whereas AAV-NP59 showed pericentral zonation in steatotic liver (Extended Data Fig. 7f and Supplementary Fig. 11c,d). These tropisms could not be explained by the presence or absence of known AAV entry factors48 (Supplementary Fig. 8b,c). A high steatosis score did not negatively impact the transduction efficiency of any of the AAV capsids we tested (Fig. 3c,d,f).

Notably, we identified a population of nonzonated hepatocytes both in normal and steatotic livers marked by the expression of SOX9, SPP1 and TACSTD2 (Extended Data Fig. 7g–i). The number of TACSTD2 (TROP2)-expressing hepatocytes increased considerably with steatosis severity, which was not paralleled by an increase in markers of proliferation (Extended Data Fig. 7j,k), suggesting that TROP2 expression in hepatocytes reflects reaction to disease, not expansion of a progenitor cell population as previously suggested19. The cells can be transduced by all capsids we tested, with AAV-LK03 being the most efficient, which highlights this hepatocyte population as a potential therapeutic target in steatotic liver disease (Extended Data Fig. 7l).

These results show that the AAV-LK03 capsid preferentially transduces periportal hepatocytes in normal human liver but lacks this zone-specific tropism in the steatotic human liver. AAV8 shows similar trends, but its periportal hepatocyte tropism is much less pronounced in human liver than in NHP liver16. Meanwhile, the AAV5 capsid has a strong tropism for pericentral hepatocytes in the steatotic human liver but transduces hepatocytes evenly in the normal human liver49.

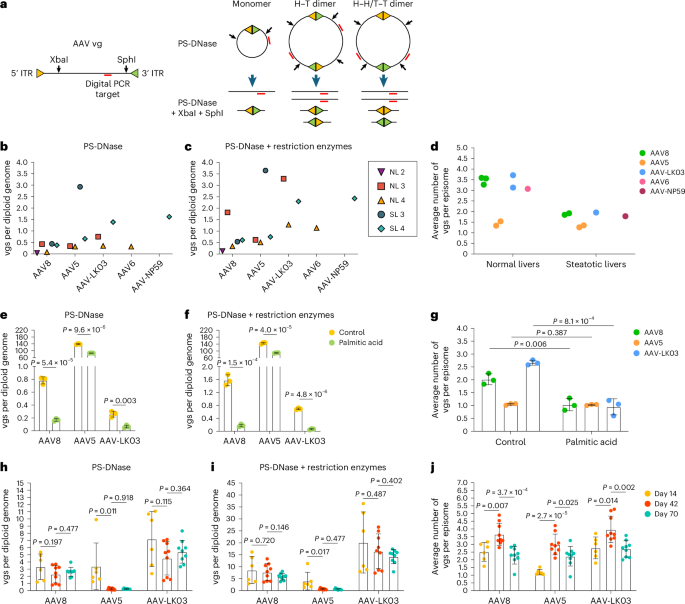

AAV capsid-specific and steatosis effects on vector episome formation

We next investigated whether steatosis impacts episome formation of AAV vectors, which is critical for long-term transgene expression50. We isolated nuclei from liver tissue from NL 2, NL 3, NL 4, SL 3 and SL 4 to quantify vector episomes using digital PCR (Fig. 4a and Methods)49 and confirmed that circular monomers and concatemers form in human livers within 73 h (Fig. 4b,c). We found fewer vgs in episomes isolated from steatotic livers than in episomes isolated from normal livers, independent of which of the five AAV capsids was used to produce the vector, suggesting that circular concatemerization of AAV vectors was compromised in steatotic livers (Fig. 4d).

a, Schematics showing predicted AAV vg structures following treatment with Plasmid-Safe DNase (PS-DNase) alone or in combination with restriction enzymes (XbaI and SphI). PS-DNase treatment allows for quantification of circular episomes by digital PCR; additional restriction enzyme treatment allows for quantification of total vector DNA (vgs) in circular episomes; H–T, head to tail; H–H, head to head; T–T, tail to tail. b,c, Quantification of circular episomes (b) and total vgs in circular episomes (c) in nuclei from segment three of human liver tissues. BmtI and SphI were used to cut vector DNA from SL 3. d, Quantification of the average number of vgs per episome in nuclei from segment three of normal livers (NL 2, NL 3 and NL 4) and steatotic livers (SL 3 and SL 4). The average number was calculated by dividing the number in c by the number in b. e–g, Quantification of circular episomes (e), total vgs in circular episomes (f) and the average number of vgs per episome (g) in total DNA from iPS cell-Heps 7 days after AAV vector transduction. Three AAV vectors were cotransduced at multiplicities of infection of 20,000 for the AAV8 capsid, 1,000 for the AAV5 capsid and 30 for the AAV-LK03 capsid. Palmitic acid was added at 200 µM every 2 days for 9 days. Values are presented as mean ± s.d. (n = 3, technical replicates). h–j, Quantification of circular episomes (h), total vgs in circular episomes (i) and the average number of vgs per episome (j) in tissue samples from FRGN mouse livers repopulated with human hepatocytes after co-injection of AAV vectors at the same dose of 4 × 1010 vgs. Values are presented as mean ± s.d. (six lobes from two mice at day 14, nine lobes from three mice at day 42 and nine lobes from three mice at day 70; biological replicates). Means were compared using two-tailed unpaired t-tests.

To confirm this result, we analyzed episome formation by vectors produced with the AAV8, AAV5 and AAV-LK03 capsids cotransduced into human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived hepatocytes (iPS cell-Heps) treated with palmitic acid, a saturated fatty acid that causes steatosis51. As a prerequisite, we ascertained that cotransduction does not impact quantification of episome formation (Extended Data Fig. 8a–c). We found that palmitic acid treatment for 7 days caused the number of episomes to decline (Fig. 4e,f). Palmitic acid had little effect on physical transduction and transgene expression, indicating that not only episomes but also linear vectors are available for transcription soon after transduction (Extended Data Fig. 8d,e). Confirming our findings in human livers, AAV8 and AAV-LK03 vectors failed to form concatemers in steatotic iPS cell-Heps, whereas the AAV5 vector was unaffected because it predominantly formed circular monomers despite a high number of transduced vgs (Fig. 4g and Extended Data Fig. 8d).

Next, we investigated long-term episome formation by AAV vectors, focusing on the distinctive effect of the AAV5 capsid, leading to predominant formation of circular monomers in human livers (Fig. 4b–d and Extended Data Fig. 8f). We analyzed AAV8, AAV5 and AAV-LK03 episomes in FRGN mice repopulated with human hepatocytes to more than 90% (ref. 52). The number of vgs in AAV8 and AAV-LK03 episomes was stable for 70 days, and they rapidly formed large concatemers (Fig. 4h–j). This finding confirms findings in livers of NHPs where concatemers formed as early as 3 days and lasted for 90 days after intravenous injection of an AAV8 vector53. By contrast, the number of vgs in AAV5 episomes declined over time, probably because of degradation, with concatemers being detectable only by day 42. The number of vgs in episomes dictated the transcriptional output at all time points for all capsids, with linear vgs probably contributing to transcription initially (Extended Data Fig. 8g,h). AAV5 episomes had the lowest transcription efficiency across all time points, contradicting previous findings in mouse liver that monomers are more efficiently transcribed than concatemers54. Episome kinetics of these capsids were similar in wild-type mice, with AAV5 showing rapid circular monomer formation followed by a steep decline in the number of vgs in episomes and concatemerization occurring only by day 40 (Extended Data Fig. 8i–l).

These results reveal that the AAV capsid influences the kinetics of vector episome formation, probably by affecting the recombination of inverted terminal repeats (ITRs)55. The AAV5 capsid causes formation of relatively unstable episomes that concatemerize more slowly than AAV8 and AAV-LK03 episomes, which translates into lower long-term transgene expression. In addition, these results identify steatosis as a capsid-independent factor impairing episome concatemerization and thereby the durability of transgene expression from AAV vectors.

AAV capsid-specific nonhepatocyte tropism and co-regulated genes

The tropism of AAV capsids for human liver cell types beyond hepatocytes is unknown, which may have contributed to complications or obscured opportunities in the clinical setting. Our integrated dataset from NL 3, NL 4, SL 3 and SL 4, including over 35,800 cells and 26 specific cell types, revealed that AAV vectors consistently transduce not only hepatocytes but also endothelial cells and monocytes/macrophages (Fig. 2c,d). We separately analyzed all endothelial cells and monocytes/macrophages to identify potential heterogeneity in transduction within these populations. From 2,759 monocytes/macrophages, we discerned seven distinct types, including scar-associated macrophages reported in fibrotic livers56 that were most prevalent in SL 3 and SL 4 (Fig. 5a,b and Extended Data Fig. 9a). We found a clear tropism for resident Kupffer cells of all capsids except AAV-LK03, with AAV6 and AAV8 being most efficient, transducing up to 13.2% and 8.6% of Kupffer cells, respectively (Fig. 5b–e).

a, UMAP of 2,759 monocytes/macrophages from four livers clustered according to cell subtype. b, Population distribution of monocyte/macrophage subtypes. c, AAV-transduced cells visualized by UMAP. d, Heat map showing percent transduction by AAV capsids of monocyte/macrophage subtypes. e, Quantification of AAV transgene mRNA-expressing Kupffer cells by scRNA-seq. f, UMAP of 2,091 endothelial cells from four livers clustered according to cell subtype; ECs, endothelial cells; LSECs, liver sinusoidal endothelial cells; PP, periportal; PC, pericentral. g, Population distribution of endothelial cell subtypes. h, AAV-transduced cells visualized by UMAP. i, Heat map showing percent transduction by AAV capsids of endothelial cell subtypes. j, Quantification of AAV transgene mRNA-expressing LSECs by scRNA-seq.

Subclustering of 2,091 endothelial cells distinguished eight subpopulations, of which the five capsids almost exclusively transduced liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs), with AAV5 and AAV8 being most efficient (Fig. 5f–j and Extended Data Fig. 9b). In steatotic livers, AAV5 transduced LSECs 3.3–5 times better than AAV8 to a maximum of 3.5%, whereas in normal livers, AAV8 was equivalent or better than AAV5 at 2% (Fig. 5j and Extended Data Fig. 9c). This unique tropism probably reflects the increase in immune-polarized LSECs in steatotic livers, which were transduced more readily by AAV5 (Fig. 5g,i). These results indicated that, as with hepatocytes, the steatotic environment increases the transduction of LSECs by AAV5. In addition, these results highlighted LSECs (the physiological source of factor VIII and von Willebrand factor) as an alternative and more physiologically relevant target than hepatocytes for hemophilia A57 or von Willebrand disease gene therapy58,59. In support of this notion, the transduction efficiency of LSEC subtypes by the AAV8 and AAV5 capsids approached or surpassed levels found in hepatocytes transduced with the same capsids (Figs. 2d and 5i). Moreover, 1.25% of total LSECs expressed MKI67 or TOP2A, which is comparable to the 1.30% of hepatocytes found to express these markers and suggests a similar turnover rate and thus AAV vector persistence between the two cell types60 (Extended Data Fig. 9d).

Finally, we sought to define potential host factors involved in or affected by transduction of the five AAV capsids in hepatocytes from NL 3, NL 4, SL 3 and SL 4 (Supplementary Data 1). We found no evidence for activation of inflammatory signaling by AAV vectors in hepatocytes (Supplementary Fig. 8d). Differential gene expression analysis of 3,749 hepatocytes uniquely transduced with one of the five AAV vectors further showed that most upregulated genes exhibit a modest increase in expression (log2 (fold change) < 1), indicating that AAV vectors do not perturb the host cell transcriptome (Supplementary Data 1). Focusing on significantly coenriched genes common to at least three capsids highlighted PIGR, which regulates the transcytosis of immune complexes for defending against viral infection61, and APOC1, a cofactor mediating hepatitis C virus infection62. CSH2 was the most significantly coenriched gene in hepatocytes transduced with the AAV8, AAV-LK03 or AAV-NP59 capsid in NL 2, NL 3 and SL 4 (Supplementary Data 1 and Supplementary Fig. 12a,b). Despite evidence that CSH2 plays a role in regulating hepatitis B virus transcription63 or in the virus defense response64, its role in AAV vector transduction is unknown.

These results define the human NPC tropism of the four AAV capsids most commonly used in clinical trials of liver gene therapy1 and a promising new capsid engineered to specifically transduce human hepatocytes34. Illustrating the value of these results, they suggest LSECs as a physiological target for gene therapy of hemophilia A or von Willebrand disease using the AAV5 or AAV8 capsid. These results also highlight capsid-specific genes potentially involved in AAV trafficking or transcription and show transcriptomic stability of hepatocytes transduced with AAV vectors.